Richard Estes Painting Central Savings Is an Example of What Kind of Art?

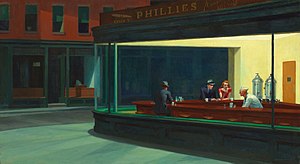

| Nighthawks | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Edward Hopper |

| Twelvemonth | 1942 |

| Medium | oil paint, sail |

| Movement | American realism |

| Dimensions | 84.1 cm (33.1 in) × 152.4 cm (threescore.0 in) |

| Location | Art Found of Chicago |

| Accession No. | 1942.51 |

Nighthawks is a 1942 oil on canvas painting by Edward Hopper that portrays iv people in a downtown diner late at night as viewed through the diner's large glass window. The light coming from the diner illuminates a darkened and deserted urban streetscape.

Information technology has been described as Hopper's all-time-known work[1] and is i of the most recognizable paintings in American art.[2] [3] Within months of its completion, it was sold to the Art Institute of Chicago on May 13, 1942, for $3,000.[4]

About the painting [edit]

It has been suggested that Hopper was inspired by a short story of Ernest Hemingway's, either "The Killers", which Hopper greatly admired,[v] or from the more philosophical "A Make clean, Well-Lighted Place".[6] In response to a query on loneliness and emptiness in the painting, Hopper outlined that he "didn't see it as specially solitary". He said "unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large urban center".[7]

Josephine Hopper'due south notes on the painting [edit]

Starting shortly afterwards their spousal relationship in 1924, Edward Hopper and his wife Josephine (Jo) kept a periodical in which he would, using a pencil, make a sketch-drawing of each of his paintings, forth with a precise description of certain technical details. Jo Hopper would then add together additional information virtually the theme of the painting.

A review of the folio on which Nighthawks is entered shows (in Edward Hopper's handwriting) that the intended proper name of the work was really Night Hawks and that the painting was completed on January 21, 1942.

Jo's handwritten notes well-nigh the painting requite considerably more particular, including the possibility that the painting's title may have had its origins as a reference to the bill-shaped olfactory organ of the homo at the bar, or that the appearance of one of the "nighthawks" was tweaked in order to relate to the original pregnant of the word:

Night + brilliant interior of cheap restaurant. Vivid items: cherry woods counter + tops of surrounding stools; lite on metal tanks at rear right; brilliant streak of jade greenish tiles 3/four across canvas--at base of operations of glass of window curving at corner. Light walls, ho-hum yellow ocre [sic] door into kitchen correct. Very skilful looking blond boy in white (coat, cap) inside counter. Girl in red blouse, brown pilus eating sandwich. Human nighttime militarist (beak) in dark suit, steel grey chapeau, blackness band, blue shirt (clean) holding cigarette. Other figure dark sinister back--at left. Light side walk outside stake light-green. Darkish red brick houses opposite. Sign beyond summit of restaurant, dark--Phillies 5c cigar. Picture of cigar. Outside of store dark, green. Note: bit of vivid ceiling inside shop against dark of outside street--at border of stretch of acme of window.[8]

In January 1942, Jo confirmed her preference for the name. In a letter to Edward's sister Marion she wrote, "Ed has just finished a very fine flick--a luncheon counter at night with 3 figures. Dark Hawks would be a fine proper name for it. E. posed for the two men in a mirror and I for the daughter. He was nearly a month and half working on it."[9] Opposite to her merits, in that location are four figures in the painting.

Ownership history [edit]

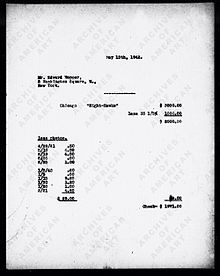

Invoice showing $1,971 going to the creative person after committee and costs

Upon completing the canvas in the late winter of 1941–42, Hopper placed it on brandish at Rehn's, the gallery at which his paintings were ordinarily placed for sale. It remained there for about a month. On St. Patrick'south Twenty-four hour period, Edward and Jo Hopper attended the opening of an exhibit of the paintings of Henri Rousseau at New York's Museum of Modernistic Art, which had been organized by Daniel Catton Rich, the manager of the Art Institute of Chicago. Rich was in attendance, forth with Alfred Barr, the director of the Museum of Modern Art. Barr spoke enthusiastically of Gas, which Hopper had painted a year earlier, and "Jo told him he merely had to go to Rehn's to see Nighthawks. In the event it was Rich who went, pronounced Nighthawks 'fine as a [Winslow] Homer', and soon arranged its purchase for Chicago."[10] The sale cost was $3,000 (equivalent to $49,750 in 2021).[4]

Location of the restaurant [edit]

The scene was supposedly inspired by a diner (since demolished) in Greenwich Hamlet, Hopper's neighborhood in Manhattan. Hopper himself said the painting "was suggested by a restaurant on Greenwich Avenue where two streets run across". Additionally, he noted that "I simplified the scene a peachy deal and made the restaurant bigger".[11]

That reference has led Hopper aficionados to engage in a search for the location of the original diner. The inspiration for the search has been summed up in the blog of one of these searchers: "I am finding information technology extremely difficult to permit go of the notion that the Nighthawks diner was a real diner, and not a total composite built of grocery stores, hamburger joints, and bakeries all cobbled together in the painter's imagination".[12]

The spot usually associated with the former location is a now-vacant lot known every bit Mulry Square, at the intersection of 7th Avenue South, Greenwich Avenue, and Westward 11th Street, about seven blocks westward of Hopper'southward studio on Washington Square. However, co-ordinate to an article by Jeremiah Moss in The New York Times, that cannot be the location of the diner which inspired the painting, considering a gas station occupied that lot from the 1930s to the 1970s.[13]

Moss located a land-use map in a 1950s municipal atlas showing that "One-time between the tardily '30s and early '50s, a new diner appeared near Mulry Square". Specifically, the diner was located immediately to the correct of the gas station, "not in the empty northern lot, merely on the southwest side, where Perry Street slants". That map is not reproduced in the Times article just is shown on Moss'southward blog.[14]

Moss comes to the conclusion that Hopper should exist taken at his word: the painting was simply "suggested" by a real-life restaurant, he had "simplified the scene a great deal", and he "made the eating place bigger". In brusque, in that location probably never was a unmarried real-life scene identical to the 1 that Hopper had created, and if one did exist, at that place is no longer sufficient show to pin down the precise location. Moss concludes, "the ultimate truth remains bitterly out of reach".[12]

In popular civilisation [edit]

Roger Brown's Puerto Rican Wedding (1969). Brown said that the café in the lower left corner of this painting "isn't set up similar an imitation of Nighthawks, but still refers to information technology very much."[fifteen]

Because information technology is so widely recognized, the diner scene in Nighthawks has served as the model for many homages and parodies.

Painting and sculpture [edit]

Many artists accept produced works that allude or respond to Nighthawks.

Hopper influenced the Photorealists of the late 1960s and early 1970s, including Ralph Goings, who evoked Nighthawks in several paintings of diners. Richard Estes painted a corner store in People's Flowers (1971), merely in daylight, with the store's large window reflecting the street and heaven.[16]

More directly visual quotations began to appear in the 1970s. Gottfried Helnwein's painting Boulevard of Cleaved Dreams (1984) replaces the three patrons with American pop culture icons Humphrey Bogart, Marilyn Monroe, and James Dean, and the attendant with Elvis Presley.[17] According to Hopper scholar Gail Levin, Helnwein connected the bleak mood of Nighthawks with 1950s American cinema and with "the tragic fate of the decade's best-loved celebrities."[xviii] Nighthawks Revisited, a 1980 parody by Cherry Grooms, clutters the street scene with pedestrians, cats, and trash.[nineteen] A 2005 Banksy parody shows a fatty, shirtless soccer hooligan in Wedlock Flag boxers continuing inebriated outside the diner, apparently having just smashed the diner window with a nearby chair.[20]

A big mural recreation of Nighthawks was painted on a defunct Chinese restaurant in Santa Rosa, California until the edifice was demolished in 2019.[21]

Literature [edit]

Several writers have explored how the customers in Nighthawks came to be in a diner at nighttime, or what volition happen side by side. Wolf Wondratschek's poem "Nighthawks: Afterward Edward Hopper'south Painting" imagines the human and woman sitting together in the diner as an estranged couple: "I bet she wrote him a letter/ Whatever it said, he's no longer the human being / Who'd read her messages twice."[22] Joyce Carol Oates wrote interior monologues for the figures in the painting in her verse form "Edward Hopper's Nighthawks, 1942".[23] A special issue of Der Spiegel included v brief dramatizations that built five different plots around the painting; one, by screenwriter Christoph Schlingensief, turned the scene into a chainsaw massacre. Erik Jendresen and Stuart Dybek too wrote short stories inspired by this painting.[24] [25]

Pic [edit]

Hopper was an gorging moviegoer and critics take noted the resemblance of his paintings to film stills. Nighthawks and works such equally Dark Shadows (1921) anticipate the look of film noir, whose evolution Hopper may have influenced.[26] [27]

Hopper was an best-selling influence on the film musical Pennies from Heaven (1981), for which product designer Ken Adam recreated Nighthawks equally a set.[28] Director Wim Wenders recreated Nighthawks as the set for a picture-within-a-film in The Terminate of Violence (1997).[26] Wenders suggested that Hopper's paintings entreatment to filmmakers because "You can ever tell where the camera is."[29] In Glengarry Glen Ross (1992), 2 characters visit a café resembling the diner in a scene that illustrates their solitude and despair.[xxx] The painting was besides briefly used as a background for a scene in the blithe movie Heavy Traffic (1973) by director Ralph Bakshi.[31]

Nighthawks as well influenced the "future noir" look of Bract Runner; director Ridley Scott said "I was constantly waving a reproduction of this painting under the noses of the production team to illustrate the look and mood I was after".[32] In his review of the 1998 film Nighttime City, Roger Ebert noted that the flick had "store windows that owe something to Edward Hopper'due south Nighthawks."[33] Difficult Processed (2005) best-selling a similar debt by setting ane scene at a "Nighthawks Diner" where a character purchases a T-shirt with Nighthawks printed on it.[34]

Music [edit]

- Tom Waits's album Nighthawks at the Diner (1975) features a title, a comprehend, and lyrics inspired by Nighthawks.[35]

- The video for Voice of the Beehive's song "Monsters and Angels", from Honey Lingers, is set in a diner reminiscent of the ane in Nighthawks, with the band-members portraying waitstaff and patrons. The band's spider web site said they "went with Edward Hopper's classic painting, Nighthawks, as a visual guide."[36]

- Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark'south 2013 single "Night Café" was influenced by Nighthawks and mentions Hopper by proper noun. Seven of his paintings are referenced in the lyrics.[37]

Theatre and opera [edit]

- Jonathan Miller's 1982 production of Verdi'southward opera Rigoletto for English language National Opera, set in 1950s New York, designed by Patrick Robertson and Rosemary Vercoe, features one street setting with a bar inspired past the Nighthawks diner.[38]

Television [edit]

- The telly series CSI: Crime Scene Investigation placed its characters in a version of the painting.[39]

- The telly bear witness Fresh Off the Boat Season 2 affiche features the title family in Nighthawks with extra Constance Wu using chopsticks.[40]

- The closing scene of Turner Classic Movies (TCM)'due south "Open All Night" intro sequence, which was used to open up overnight moving-picture show presentations from 1994 to 2021, is based on Nighthawks. [41]

- The American telly serial Shameless features the Nighthawks painting, in a tardily season 11 arc where Frank pulls off his final "ICOE" heist. [42]

Calibration model [edit]

A number of model railroaders, nearly notably John Armstrong, have recreated the scene on their layouts.[43]

The theater lighting manufacturer Electronic Theatre Controls has a human sized calibration model of the diner in the lobby of their headquarters in Middleton, Wisconsin. It is used equally a reception area for the building.[44]

Parodies [edit]

Nighthawks has been widely referenced and parodied in popular culture. Versions of it have appeared on posters, T-shirts and greeting cards as well as in comic books and advertisements.[45] Typically, these parodies—like Helnwein'southward Boulevard of Broken Dreams, which became a popular poster[eighteen]—retain the diner and the highly recognizable diagonal composition only replace the patrons and attendant with other characters: animals, Santa Claus and his reindeer, or the corresponding casts of The Adventures of Tintin or Peanuts.[46]

I parody of Nighthawks even inspired a parody of its own. Michael Bedard's painting Window Shopping (1989), part of his Sitting Ducks series of posters, replaces the figures in the diner with ducks and shows a crocodile outside eying the ducks in anticipation. Poverino Peppino parodied this image in Boulevard of Broken Ducks (1993), in which a contented crocodile lies on the counter while iv ducks stand outside in the rain.[47]

See besides [edit]

- 100 Great Paintings, 1980 BBC series

References [edit]

Notes

- ^ Ian Chilvers and Harold Osborne (Eds.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art Oxford University Press, 1997 (2nd edition), p. 273, ISBN 0-nineteen-860084-4 "The central theme of his work is the loneliness of city life, generally expressed through 1 or two figures in a spare setting - his all-time-known work, Nighthawks, has an unusually large 'cast' with iv."

- ^ Hopper's Nighthawks, Smarthistory video, accessed April 29, 2013.

- ^ Brooks, Katherine (July 22, 2012). "Happy Altogether, Edward Hopper!". The Huffington Mail service. TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc. Retrieved May v, 2013.

- ^ a b The sale was recorded past Josephine Hopper equally follows, in book II, p. 95 of her and Edward's periodical of his art: "May thirteen, '42: Chicago Art Institute - iii,000 + return of Compartment C in commutation every bit function payment. one,000 - ane/3 = 2,000." See Deborah Lyons, Edward Hopper: A Journal of His Work. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1997, p. 63.

- ^ Gail Levin in "Interview with Gail Levin"

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 44

- ^ Kuh, Katherine (1962). "The Artist's Vocalism: Talks With Seventeen Artists". Harper & Row. p. 134. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ Meet Deborah Lyons, Edward Hopper: A Periodical of His Work. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1997, p. 63

- ^ Jo Hopper, in letter to Marion Hopper, January 22, 1942. Quoted in Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography. New York: Rizzoli, 2007, p. 349.

- ^ Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography. New York: Rizzoli, 2007, pp. 351-2, citing Jo Hopper'due south diary entry for March 17, 1942.

- ^ Hopper, interview with Katharine Kuh, in The Artist's Vocalism: Talks with Seventeen Modern Artists. 1962. Reprinted, New York: Da Capo Press, 2000, p. 134.

- ^ a b Jeremiah Moss (June ten, 2010). "Jeremiah's Vanishing New York: Finding Nighthawks, Coda". Jeremiah's Vanishing New York . Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ Moss, Jeremiah (July 5, 2010). "Nighthawks State of Mind". The New York Times . Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ^ Moss, Jeremiah (June 9, 2010). "Finding Nighthawks, Function iii". Jeremiah's Vanishing New York (blog) . Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ^ Levin, 111–112.

- ^ Levin, Gail (1995), "Edward Hopper: His Legacy for Artists", in Lyons, Deborah; Weinberg, Adam D. (eds.), Edward Hopper and the American Imagination, New York: W. W. Norton, pp. 109–115, ISBN0-393-31329-8

- ^ "Boulevard of Broken Dreams 2". Helnwein.com. October xv, 2013. Archived from the original on July 4, 2009. Retrieved Baronial xviii, 2014.

- ^ a b Levin, 109–110.

- ^ Levin, 116–123.

- ^ Jury, Louise (October 14, 2005), "Rats to the Arts Establishment", The Independent

- ^ "Prominent Santa Rosa murals to exist demolished". Santa Rosa Press Democrat. January xvi, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Gemünden, 2–5, xv; quotation translated from the German language by Gemünden.

- ^ Updike, John (2005). "Hopper's Polluted Silence". Still Looking: Essays on American Art . New York: Knopf. p. 181. ISBNane-4000-4418-9. . The Oates poem appears in the anthology Hirsch, Edward, ed. (1994), Transforming Vision: Writers on Art , Chicago, Illinois: Art Institute of Chicago, ISBN0-8212-2126-4

- ^ Gemünden, v–six.

- ^ Janiczek, Christina (Dec 5, 2010). "Volume Review: Coast of Chicago by Stuart Dybek". Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ a b Gemünden, Gerd (1998), Framed Vsions: Popular Civilization, Americanization, and the Contemporary High german and Austrian Imagination, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Printing, pp. 9–12, ISBN0-472-10947-ii

- ^ Doss, Erika (1983), "Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, and Flick Noir" (PDF), Post Script: Essays in Film and the Humanities, 2 (ii): fourteen–36, archived from the original (PDF) on Oct 16, 2009

- ^ Doss, 36.

- ^ Berman, Avis (2007), "Hopper", Smithsonian, 38 (4): 4, archived from the original on July 11, 2007

- ^ Arouet, Carole (2001), "Glengarry Glen Ross ou fifty'autopsie de 50'image modèle de l'économie américaine" (PDF), La Voix du Regard (14), archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2007

- ^ "Rotospective: Ralph Bakshi'due south 2d Picture show is Loftier on Detail, Consistency and Realism | Agent Palmer".

- ^ Sammon, Paul M. (1996), Future Noir: the Making of Blade Runner, New York: HarperPrism, p. 74, ISBN0-06-105314-seven

- ^ "Dark Urban center". ebertfest.com. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ Chambers, Bill, "Hard Candy (2006), The Male monarch (2006)", Film Freak Central, archived from the original on September 26, 2007, retrieved August 5, 2007

- ^ Thiesen, x; Reynolds, E25.

- ^ "Biography". Voice of the Beehive Online. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Premiere: OMD, 'Night Café' (Vile Electrodes 'B-Side the C-Side' Remix)". Slicing Up Eyeballs. August 5, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- ^ "Verdi'south Rigoletto at ENO". Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ Theisen, Gordon (2006), Staying Up Much Too Late: Edward Hopper's Nighthawks and the Dark Side of the American Psyche, New York: Thomas Dunne Books, p. 10, ISBN0-312-33342-0

- ^ Slezak, Michael (September 11, 2015). "Fresh Off the Boat's Season ii Poster: The Huangs Give Us an Art-Attack".

- ^ "Exopolis Revives Vintage Edward Hopper Inspired Promo for Turner Classic Movies".

- ^ "Shameless' end-of-life storytelling continues to disappoint, not that we expected otherwise".

- ^ "And Now for Something Completely Different". O Judge Railroading On-Line Forum . Retrieved September eighteen, 2015.

- ^ "Secrets of ETC's Town Square". Et Cetera, Electronic Theatre Controls. Retrieved Oct 9, 2018.

- ^ Levin, 125–126. Reynolds, Christopher (September 23, 2006), "Lives of a Diner", Los Angeles Times, pp. E25

- ^ Levin, 125–126; Thiesen, 10.

- ^ Müller, Beate (1997), "Introduction", Parody: Dimensions and Perspectives, Rodopi, ISBN904200181X

Bibliography

- Cook, Greg, "Visions of Isolation: Edward Hopper at the MFA", Boston Phoenix, May 4, 2007, p. 22, Arts and Entertainment.

- Spring, Justin, The Essential Edward Hopper, Wonderland Press, 1998

External links [edit]

- Nighthawks at The Art Institute of Chicago

- Sister Wendy'south American Masterpieces discussion of Nighthawks at The Artchive.

- Jeremiah Moss (June vii, 2010). "Finding Nighthawks". Jeremiah's Vanishing New York.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nighthawks_(painting)

0 Response to "Richard Estes Painting Central Savings Is an Example of What Kind of Art?"

Postar um comentário